Boundary Thinking: How Good Leaders Know When to Listen, Decide, and Communicate

The leadership skill that bridges the gap between humility and decisiveness - helping you know when you've gathered enough input to act.

Why Do Smart Leaders Still Struggle to Make Good Decisions?

Sarah had been VP of Operations for three years when the supply chain issue landed on her desk. She did what good leaders do: she called a meeting. She pulled in logistics, finance, and customer success. She asked great questions. People said she was "really listening."

Six weeks later, nothing had changed.

Her team wasn't frustrated with her intelligence or her care. They were frustrated because all that listening had produced exactly zero direction. The problem wasn't going away on its own, and neither was the quiet, creeping sense that maybe Sarah didn't actually know what to do.

Here's what's brutal about modern leadership: we're supposed to be humble and decisive. We're supposed to listen deeply and act quickly. Stay open to input and show unwavering confidence.

Most leadership advice treats these as separate virtues. Be more humble! Be more decisive! But nobody tells you what to do when those two things feel like they're ripping you in half.

There's a skill that lives between them. I call it boundary thinking. And once you see it, you can't unsee it.

What Does Humility Actually Look Like in Leadership?

Let's clear something up first: humility is not waiting your turn to speak. It's not nodding politely while secretly running your own script.

Real humility is the working assumption that you're standing in a dark room with a flashlight, and you can only see what's directly in front of you.

When Marcus took over as head of product, he inherited a feature roadmap that looked airtight. Engineering loved it. His predecessor had championed it. But Marcus had this nagging feeling he couldn't name.

So he started asking questions that felt almost too basic. He asked customer success what they were hearing in support tickets. He asked sales what deals were stalling. He asked the most junior designer on the team what confused her about the user flow.

Turns out the roadmap was solving last year's problem. The market had shifted. Customers were asking for something simpler, not more complex. Marcus didn't know that when he started asking. But humility gave him permission not to know.

That's what humility does. It expands the borders of what you can see. It turns your flashlight into a floodlight.

The leaders who do this well don't ask questions to look collaborative. They ask because they genuinely want to understand the shape of something before they touch it. And their teams can feel the difference.

But humility has a limit. Once you've expanded what you can see, leadership demands you move.

Why Is Decisiveness Just as Important as Humility?

Here's what nobody tells you about listening: it has a half-life.

At first, when you start asking people for input, they lean in. They appreciate being heard. But if nothing happens — if all that input just evaporates into the ether — they stop offering it.

I watched this happen to a manager I used to work with. He was a capable leader. He prided himself on listening. He would genuinely consider every angle. He would never hesitate to set up a meeting and bring people in to discuss the important matters. But he set up so many meetings, and listened so much, so carefully that by the time he was ready to decide, the moment had passed.

His team started making jokes. "Let's bring it to Dan — he'll have a meeting about it." They didn't say it with affection.

What Dan didn't realize is that indecision is a decision. It's just the worst kind, because it lets the world decide for you. Opportunities close. Competitors move. Small problems compound into crises. And your team starts to wonder if you're really leading at all.

Decisiveness isn't about being right. It's about accepting that at some point, more information won't make the picture clearer — it'll just make you more tired.

The best leaders I know treat decisions like an act of service. They know their team needs a direction, even if it's not perfect. Because a good decision executed with commitment will usually beat a perfect decision that arrives too late.

What Happens When Leaders Lean Too Far to One Side?

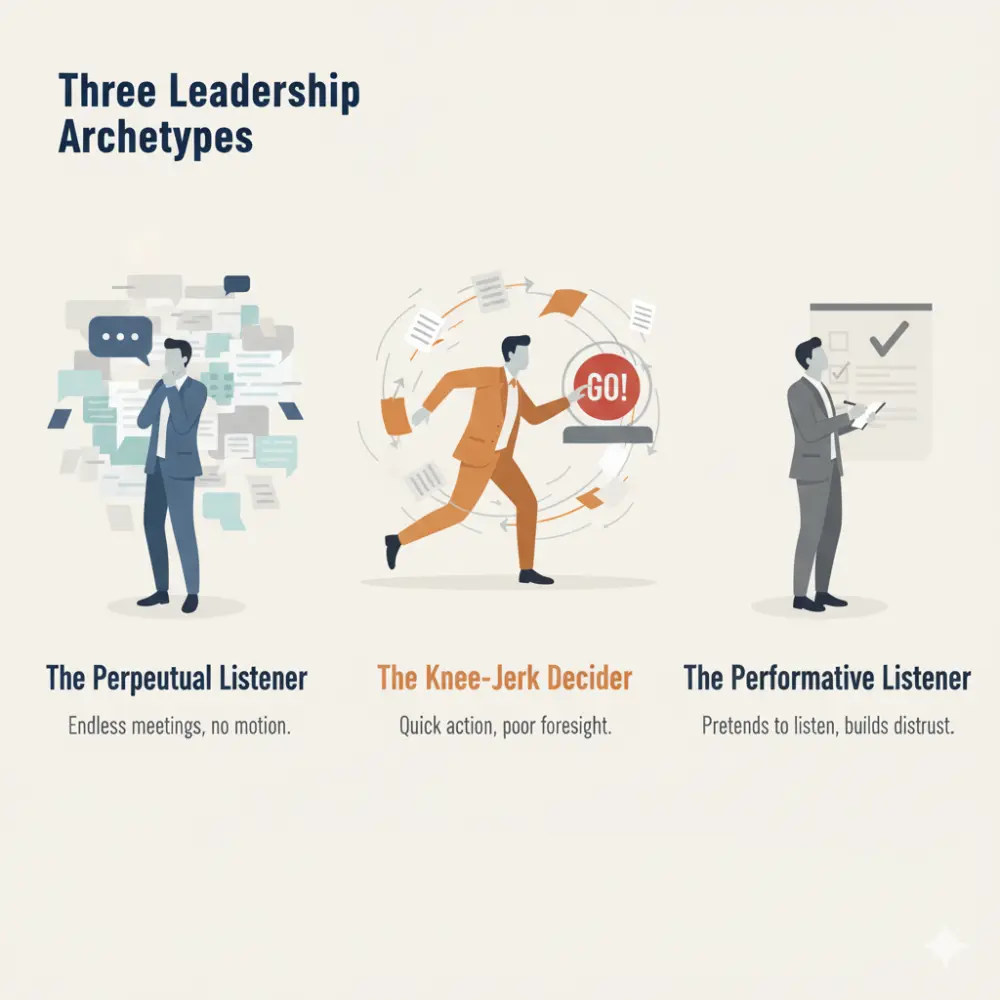

You've probably worked for all three of these people.

1. The Perpetual Listener

is easy to like at first. They're humble, curious, considerate. Meetings with them feel collaborative. But after a while you notice that nothing ever lands. Every decision spawns three more questions. Every answer requires another round of input. At some point you stop preparing for meetings because you know your ideas will just get absorbed into the fog. These leaders mistake process for progress. Their teams don't respect them less — they just stop expecting anything from them.

2. The Knee-Jerk Decider

has the opposite problem. They decide fast, speak confidently, and everyone knows where they stand. Except half the time, they're standing in the wrong place. They'll greenlight a campaign without asking marketing if they have bandwidth. They'll commit to a deadline without checking if it's technically possible. Then, two weeks later, they're surprised when everything's on fire. Their team learns to work around them, not with them. And the leader wonders why nobody brings them problems anymore — it's because they've learned those problems will just become bigger problems.

3. The Performative Listener

is the most corrosive of the three. They'll schedule the input session, take the notes, nod thoughtfully. But you can tell they've already decided. Maybe they say "yes, and..." but then steer back to their original point. Maybe they ask for feedback but get defensive the moment someone offers it. Their team learns to read the room and tell them what they want to hear. Honesty dies quietly.

What all three get wrong is the same thing: they think humility and decisiveness are opposites. They're not. They're phases. The question isn't which one you are. It's whether you know when to shift from one to the other.

How Do You Bridge the Gap Between Listening and Acting?

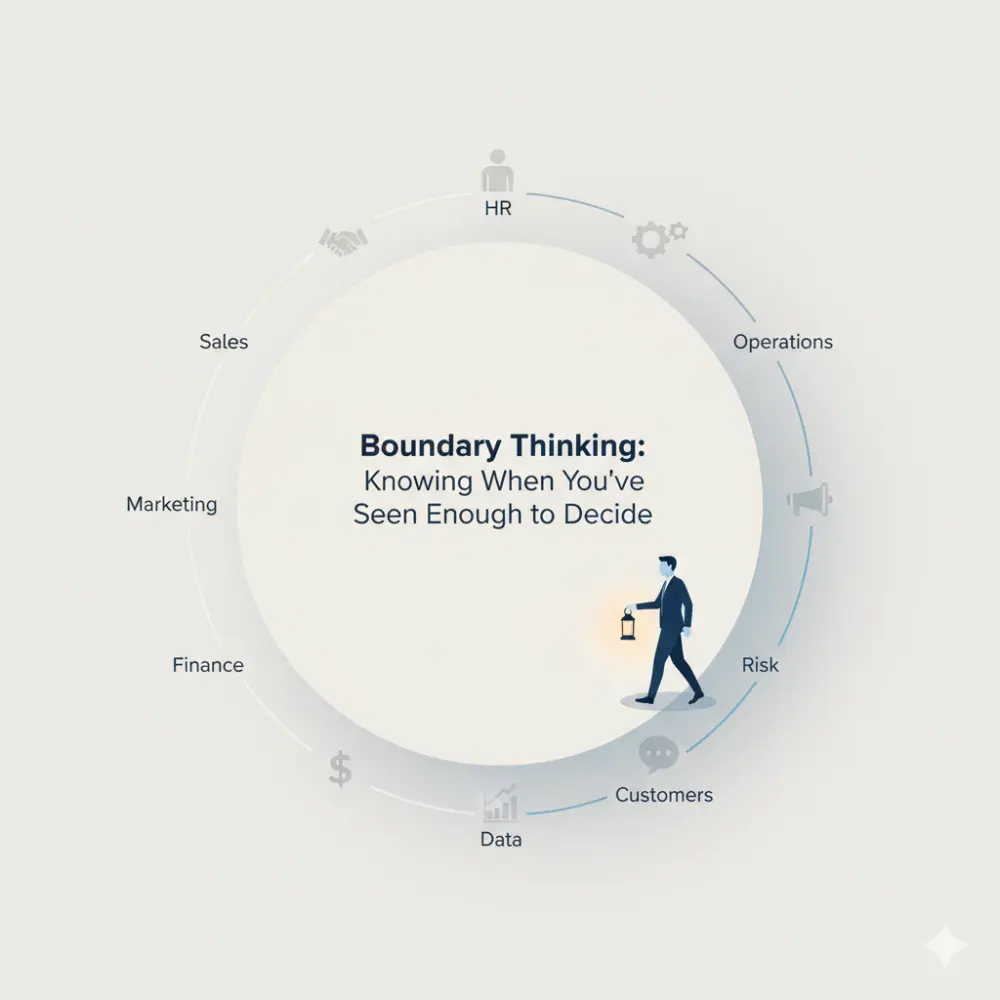

This is where boundary thinking comes in, and it's simpler than it sounds.

Imagine you're trying to understand the shape of a sculpture in the dark. You can't see the whole thing at once, so you run your hand along its edges. You start at one point and trace the surface — smooth here, rough there, a sharp corner, a gentle curve. You keep going until your hand arrives back where it started.

That's when you know you've felt the whole thing.

Boundary thinking works the same way. You walk the perimeter of a decision. You explore its edges — the people it affects, the risks it carries, the trade-offs it demands — until you've circled back to where you began.

Take Jennifer, a VP who was facing pressure to pivot her company's go-to-market strategy. The technology had evolved. Competitors were moving into their space. The executive team wanted to shift from selling to enterprises to targeting mid-market companies — a completely different motion.

Jennifer didn't start by building a new strategy deck. She started at the edges.

She talked to sales about what deals they were actually closing versus chasing. She asked marketing what messages were resonating and where leads were going cold. She pulled in customer success to understand which clients were thriving and which were struggling. She asked engineering what the platform could realistically handle at different scales. She even talked to finance about unit economics at various customer sizes.

At first, every conversation opened new questions. Sales wanted one thing. Marketing saw different opportunities. Engineering had concerns no one had considered.

But after two weeks of circling the problem, something shifted. The sales feedback started connecting to what customer success was seeing. The marketing data lined up with the financial models. Engineering's constraints actually clarified which segment made sense. Jennifer wasn't hearing new information anymore — she was hearing the same shape described from different angles.

That's when she knew she'd walked the full circle.

Boundary thinking didn't give Jennifer the answer. It gave her confidence that she was ready to decide.

You'll feel it when it happens. The room's energy changes. People stop asking "what if?" and start asking "when?" The conversation shifts from exploration to impatience. Someone will say, "So what are we actually going to do?"

That's your inflection point. That's when humility has done its work, and decisiveness becomes the next right move.

Boundary thinking doesn't tell you what to decide. It tells you when you're ready.

Why Communicating Your Decision Is Part of the Decision Itself

A lot of leaders think the hard part is making the call. It's not.

The hard part is bringing people with you.

I used to work with an executive who made smart decisions, but he made them alone. He'd disappear into his office, think it through, and emerge with a verdict. No context, no explanation, just "here's what we're doing."

His team hated it. Not because they disagreed with his decisions — half the time they would've chosen the same thing — but because they had no idea how he got there. It felt arbitrary. It felt like their input hadn't mattered.

Compare that to another leader I knew, Elena. When she made a tough call, she'd bring the team together and walk them through it. "Here's what I heard from sales. Here's what finance said we could afford. Here's the risk I'm choosing to take, and why." She didn't ask for permission. But she gave people a map of her thinking.

The result? Even when people disagreed, they trusted her. They knew she'd listened. They knew she'd weighed the options. And because they understood her reasoning, they could support the decision — or at least predict how she'd approach the next one.

Communication isn't about defending yourself. It's about closing the loop you opened when you started listening.

You don't owe people a dissertation. But you owe them enough to show that their input landed somewhere real.

How to Practice Boundary Thinking in Everyday Leadership

If you want to try this, here's how it works in practice.

- Start by defining the decision clearly. Not the topic, the actual choice. "Should we expand into a new market?" is too broad. "Should we prioritize market A or market B in Q3?" is a decision.

- Next, map the edges. Who's affected by this? What are the constraints — budget, time, people, risk? What happens if you do nothing? Write it down if it helps. Just get clear on what the perimeter looks like.

- Then, walk the circle. Talk to the people at each edge. Not to gather votes — to understand perspectives. Listen for patterns. When you hear the same concern from three different people in three different roles, that's not coincidence. That's an edge you need to respect.

- At some point, you'll spot the inflection point. New input stops changing your understanding. People stop contributing insights and start waiting for direction. The cost of delay becomes obvious. That's when you know.

- Finally, decide and explain. Make the call. Then tell people how you got there. You don't need to justify every detail, but give them the thread they can follow.

If it helps, picture it like this: you're walking the perimeter of a property before you build. You don't walk forever. But you don't stop at the first corner either. You complete the loop. Then you know where to dig.

The Art of Coming Full Circle

Leadership isn't knowing everything. It's knowing when you've learned enough to move.

I think that's what separates the leaders people trust from the ones people tolerate. The trusted ones don't pretend to have all the answers, but they also don't hide behind endless questions. They walk the edges. They complete the circle. And then they take the next step.

Boundary thinking isn't a formula. It's a rhythm. Listen until you've seen the whole shape. Then act before the moment passes. And bring people with you by showing them you were actually listening.

So next time you're stuck between gathering input and making the call, ask yourself: have I walked the edges? Have I come full circle?

Because once you have, the decision isn't the hard part anymore.

Leading is.